Nan Huai-ch’in’s Recollections of Li Zongwu

南懷瑾對厚黑學教主李宗吾的回憶

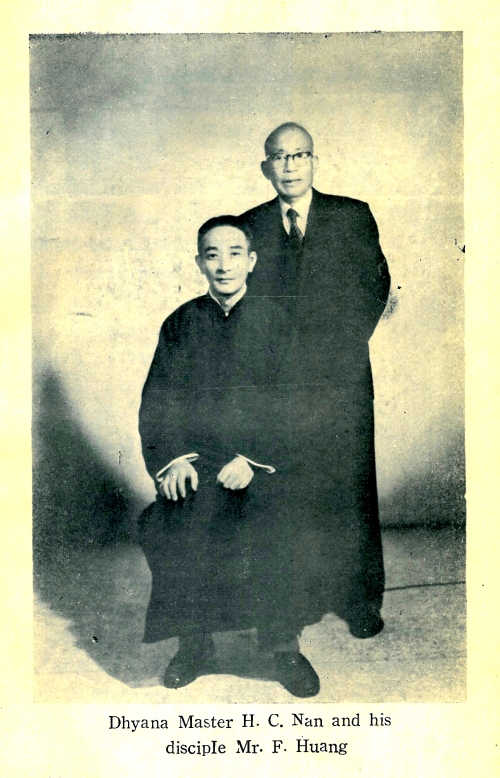

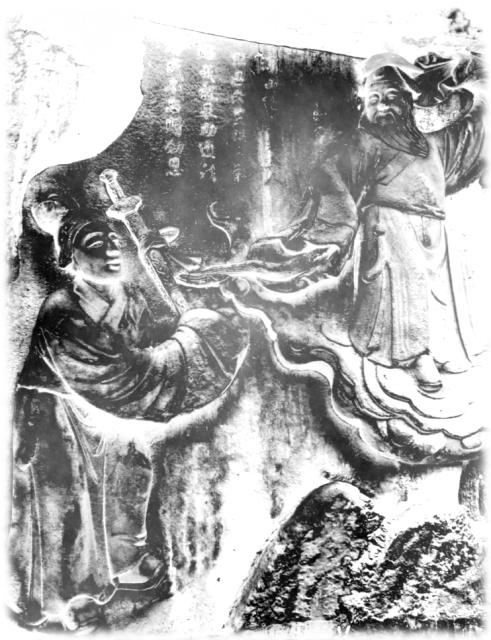

Statues of Nan Huai-ch’in (left) and Li Zongwu (right).

In his youth, Master Nan Huai-ch’in was in the habit of seeking out all manner of spiritual masters, martial arts masters, and educated people from whom to learn. One such person was the ‘founder of Thick Black Theory,’ Li Zongwu, of whom Master Nan has left this affectionate portrait, presumably written some time in the 1990s, included in recent editions of Li’s Collected Works. This depiction is in stark contrast to the image given by Li’s written work, that of a cynical, embittered contrarian.

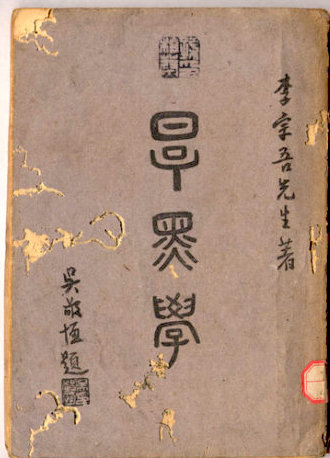

An early edition of Li Zongwu’s book

In recent years, Li Zongwu’s book Thick Black Theory has become something of a bestseller in Taiwan, Hong Kong as well as mainland China, where many people like to read it. But, contemporary readers quite likely do not understand the historical background to this work, and fewer yet know of Li Zongwu himself. Li Zongwu was a man from Sichuan, who called himself ‘the Founder of Thick Black Theory.’ Thick Black Theory means having a thick skin and a black heart.

I spent some time with Li Zongwu and had a connection with him, and in my mind, Li Zongwu was not in the slightest either ‘thick’ or ‘black.’ In fact, it could even be said that he was very kind-hearted.

I came to know Li Zongwu just before the war against Japan, I don’t recall precisely when. At that time, I was in Chengdu. Chengdu is the capital of Sichuan, and was not at all a big city like Hong Kong, where the pace of life is so fast. In my mind, everyone took life at a leisurely pace, and even until now, I still cherish those memories of Chengdu.

When I moved to Chengdu from Zhejiang, I had just turned twenty years old. Us outsiders foreign to the province were called ‘Southerners,’ and the locals weren’t too fond of us. At that time, I wanted to learn Taoism with all my heart, as well as ‘flying sword kung fu’ in order to go fight the Japanese.

So I often went to visit famous and cultured people, and those who had kung fu skills. In Chengdu at the time, there was a small park, Shaocheng Park, which had a lot of teahouses and chess tables. You could brew a pot of tea and sit there half the day, or all day long, and when you left, you paid. If you had to leave to go do something, you could leave the lid upside-down on the pot of tea, and the owner of the teahouse would leave it there until you came back. If you hadn’t got any money to drink tea, that was alright too. When the owner asked you what you wanted to drink, you could just ask for a glass, and they would bring you a glass of water. I don’t think we’ll see this kind of rural atmosphere ever again.

Shaocheng Park was the gathering place for the famous literati, the old fogeys and young diehards. You would often see people wearing old-style scholar’s robes and cotton shoes, all manner of eccentric characters. These were exactly the kind of people I was looking for, so I became a frequent visitor to the park.

For the people there, I was just a young blow-in. I wore a Sun Yat-sen style suit and I was from Zhejiang, the same place as Chiang Kai-shek. Some people were suspicious of me at first, thinking that I had been sent there by Chiang. After a while, people began to slowly understand that I was there to learn, their suspicions faded, and I began to make friends with some of these older people.

One day, I was at Shaocheng Park drinking tea and playing chess with some of these older gentlemen, when a man walked in. He was very tall, hunched over and wore a felt hat. He looked rather peculiar, like someone from ancient times. When they saw him come in, everyone nodded and said hello. I asked my friend Mr Liang who that was, and he said, “You don’t know who he is? He’s the founder of Thick Black Theory, Li Zongwu. He’s very famous in Sichuan.” Mr Liang then told me Li Zongwu’s story, and I said I really wanted to meet him, so I asked Mr Liang to introduce us. Mr Liang brought me over and introduced me to Li Zongwu, saying, “This Nan lad, he’s not from around here, but he’s a young friend of mine.” I quickly said, “I have long heard of your esteemed name,” even though I had only just heard of it! This kind of faux politeness is sometimes necessary.

The founder of Thick Black Theory invited us to sit down and have some tea and a chat. Our so-called chat consisted of us sitting there and listening to him expound his theories, talk about the Japanese occupation, listen to him curse the Sichuan Army and listen to him curse such and such a person as being worthless. That was my first time meeting the founder of Thick Black Theory, but later, I would often meet him in Shaocheng Park.

One time, the founder of Thick Black Theory told me: “I see you have heroic ideas, and in the future you will be able to make a difference. However, I will teach you a way to become a hero even quicker! If you want to be successful and famous, you have to curse people, curse those who are already famous. You needn’t curse anyone else though, just curse me, Li Zongwu, that good-for-nothing bastard! In that way you will succeed. However, all the while you must paste on your forehead a sheet of paper extolling Confucius, while you hold a tablet honouring me enshrined in your heart!”

I didn’t take his advice, so I never made a name for myself.

One time, I said to him: “Teacher, please don’t speak any more of this Thick Black Theory, please stop insulting people.” He said: “I do not insult people casually. Every one of those people has a thick face and a black heart. I am only ripping the mask off.”

I said: “I heard that the Central Government is starting to pay attention to you, and that there are people out to get you.”

He said: “My boy, you don’t understand. Einstein and I are the same age. He invented the theory of relativity and now he is a world-renowned scientist. Me, I have not even become famous in Sichuan or Chengdu. I hope they arrest me, I’ll become world-famous as soon as I’m sitting in prison.”

In the end, Li Zongwu wasn’t arrested, and thus never became world-famous.

He once said to me: “My luck isn’t good, unlike Cai Yuanpei or Liang Qichao.” Yet, his book on Thick Black Theory has been popular for a half century now. Many people like to read it, something I think he himself never foresaw.

His title of ‘Founder of Thick Black Theory’ was entirely self-styled: he never had a “church,” an organisation, nor a single follower. He was a rather lonely, solitary man.

At the time, many people liked to read his books, but not many people dared to have anything to do with him, being afraid of getting on his bad side. Not me though, I was not afraid and I still often met with him.

After a year or two, a friend of mine, a monk I’d known from Hangzhou, passed away in Ziliujing, now called Zigong. As I owed him a debt of gratitude, I decided to go to Ziliujing to pay my respects. My good friend, a monk called Qianji, also accompanied me.

We walked for eight days, from Chengdu to Ziliujing, found the tomb of our friend, burnt incense and bowed. From Ziliujing to Chengdu would be another eight days trek, and we had gone through almost all of our travel budget and were starting to get worried.

Just then a thought occurred to me: the founder of Thick Black Theory, Li Zongwu, was from Ziliujing. As Li Zongwu was well-known, as soon as we asked where his address was, we found out. His courtyard house was quite large, and the gate was wide open. In the past, it was like that in the countryside, the doors were open from morning till night, not like Hong Kong nowadays, where the doors are always strictly closed.

We called for him from the doorway, and the founder of Thick Black Theory himself came out to greet us. He was very happy to see me, and asked: “What are you doing out here?”

I told him I had come to see off a dead friend. He misunderstood me, thinking I was teasing him, and said: “I’m not dead yet!”

I quickly explained myself to him, and as soon as he saw we were as ravenous as wolves, he immediately had a dinner prepared for us. A chicken was killed, fish were fished out of the pond, fresh vegetables were prepared, and we had an authentic Sichuan meal. After having our fill of food and drink, I opened my mouth to ask him if we could borrow some money. I said: “‘One does not enter the Buddha hall without reason,’ I am afraid I must bother you about something. I am out of travel money to get back to Chengdu.”

He said: ”How much do you need?”

“Ten silver dollars,” I replied.

He got up and went to a cabinet in the living room and took an envelope and gave it to me. I reckoned that there was more than ten dollars in there and asked how much. There were twenty dollars in there. I told him that that was too much, that I only needed ten. He insisted that I take twenty. I said I didn’t know when I could repay him, but he said to just take it and spend it first, and we could figure out the rest later.

Judging from this small matter of borrowing money, we can see that the founder of Thick Black Theory was a decent man, not ‘thick’ or ‘black’ in the slightest, but even very sincere and very kind.

After we had finished dinner and were chatting, he suddenly asked me not to return to Chengdu, but to stay on a while. I asked: “Stay to do what?”

He said: “Don’t you like martial arts? You are here to learn, no? There is a martial arts master here, Master Zhao, his kung fu is amazing.”

He then told me about this Master Zhao: “He was born a cripple, but his kung fu is excellent, especially his ‘light skill.’ He could put on a new pair of shoes and walk a mile in the snow and there won’t be a speck of mud on them. He once had a disciple whose kung-fu was also very good, but who misused what he had learned to do bad things. One night the disciple crept over a wall into a house and raped a woman. In a rage, Master Zhao put an end to his kung fu, maiming him, and he hasn’t taken on any more students since.”

Li Zongwu felt it would be a shame if Master Zhao’s kung fu were to be lost, and so encouraged me to stay on and practice. I asked how I could become his student if he was refusing to accept new disciples.

Li Zongwu replied that it was not the same, as I was from Zhejiang, and Master Zhao had learned his kung fu from a couple from Zhejiang, and that if he were to recommend me, I was sure to be accepted.

He said: “Study martial arts with Master Zhao for three years, develop some martial skill, and in the future, being a warrior won’t be so bad!”

He also said that he would be pay the tuition fees for the full three years, taking care of all expenses. As I saw he was being sincere, I could not refuse him to his face. Learning martial arts was very attractive to me, but three years was too long. I asked for time to consider the matter.

That night, Qianji and I went back to the inn to spend the night. Early the next morning, Li Zongwu showed up to persuade me to stay on and learn martial arts, and in the end, I had to turn him down.

He immediately regretted it, and said: “What a pity, what a pity.”

And I returned to Chengdu.

Soon thereafter, I went on retreat for three years, cutting off all contact with the outside world, not knowing the news nor the great changes taking place out in the world. There was only one young monk who would come back up the mountain from picking rice, who occasionally brought back a little news. This monk was not from the area, and didn’t really care about the war with Japan, so I heard nothing at all about that. One day, the young monk came back, saying: “The founder of Thick Black Theory, Li Zongwu, has died.” When I heard this, I felt deeply saddened. I had borrowed twenty silver dollars from him and would never be able to pay him back. So, every day I recited the Diamond Sutra for him, in order to help him “cross over.”

Later, I heard he had died peacefully at home in bed.

– Nan Huai-ch’in

Li Zongwu (1879-1943)

You must be logged in to post a comment.