The Sixth Patriarch of Zen:

Clarifying the Mind, Seeing its Essential Nature

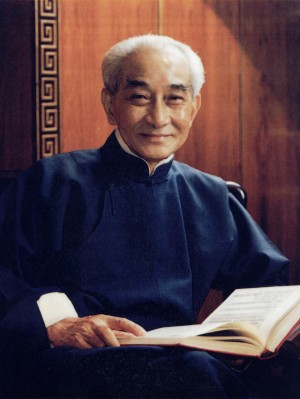

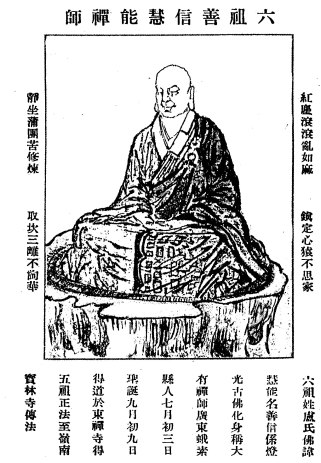

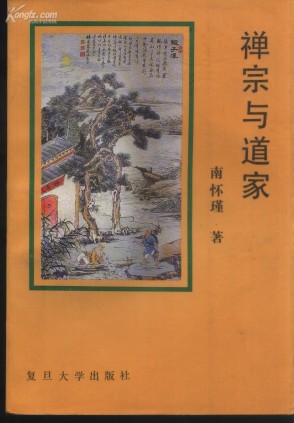

The Platform Sutra, or Altar Sutra, of the Sixth Patriarch of Zen, Huineng, is one of the foundational works of the Zen school. As translator Thomas Cleary notes in his preface to his translation of “the Sutra of Hui-neng“: “Hui-neng characterized his teaching as the teaching of immediacy, based on direct insight into the essential nature of awareness. As a testimony of his eminent place in Zen tradition, the record of Hui-neng’s life and lectures is the only such document to be dignified with the title of sutra, or “scripture”, the word traditionally reserved, in Buddhist literature, for the teachings of a buddha.” Master Nan Huai-chin (Nan Huaijin, 南懷瑾), one of the most revered lay Buddhist teachers of recent times, in his “Story of Chinese Zen“, provides a succinct summary on the background of the Platform Sutra before explaining the technical aspect of Zen meditation in plain language.

* * *

* * *

The Sixth Patriarch of Zen

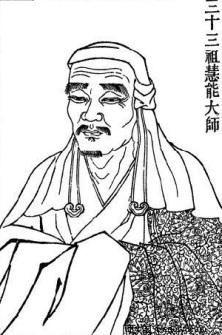

The stories about Master Hui-neng, the sixth patriarch of Chinese Zen, are favorite topics for discussion among people who lecture on Zen and the history of Chinese philosophical thought. I will present a brief introduction to his tale and then discuss several misunderstood issues therein. Great Master Hui-neng was surnamed Lu in lay life. His ancestors were from Fan-yang (in Hopei, north China), but during the Wu-te era of the reign of Emperor Kao-tsu of the T’ang dynasty (618-626) his father was assigned to a post in Kuang-tung (Canton) province. At the age of three he lost his father, and his mother resolutely took care of him alone until he grew up. Hui-neng’s family was poor and gathered wood for a living. One day as Hui-neng was carrying a load of kindling to market, he happened to hear someone reciting the Diamond Sutra. When the recitation reached the passage that says, ”One should enliven the mind without dwelling on anything,” Hui-neng attained a degree of realization. The man who was reciting the sutra told him that it was a Buddhist scripture that the fifth patriarch of Zen, Hung-jen, who was teaching in Huang-mei (Hupei), always instructed people to read. Hui-neng then contrived a way to go to Huang-mei to seek to learn to practice Zen. (At that time he had not yet left society to become a monk.) When the fifth patriarch, Zen Master Hung-jen, first saw him, he asked, “Where do you come from?” Hui-neng answered, “From Ling-nan.” The fifth patriarch then asked, “What do you want?” “I only seek to become a Buddha.” “People from Ling-nan have no Buddha nature; how can you become a Buddha?” Hui-neng said in reply, “People may be from the south or the north, but how could the Buddha nature have any east or west?” Hearing this, the fifth patriarch told Hui-neng to go to work with the rest of the people there. The future patriarch said, “My own mind always produces wisdom. Not straying from one’s own nature is itself a field of blessings. What would you have me do?” The fifth patriarch saw that his basic nature was extremely sharp, and told him to go pound rice in the mill, so Hui-neng went and labored there for eight months. Then one day the fifth patriarch announced that he was going to hand on his robe and bowl and would choose someone to inherit the rank of patriarch. Therefore, he told everyone to present an expression of their mental attainment. Now at this time there were over seven hundred monks learning Zen from the fifth patriarch. Among them was a chief elder named Shen-hsiu, who had thoroughly studied both Buddhist and non-Buddhist classics and was looked up to by everyone in the community for his learning. He knew everyone was counting on him, so he wrote a verse on the wall of the hallway, saying,

The body is the tree of enlightenment,

The mind is like a clear mirror on a stand.

Diligently wipe it off again and again,

Don’t let it gather dust.

When the fifth patriarch had seen this verse, he said, “If people of later generations cultivate practice in accord with this, they will also attain superior results.” But when Hui-neng heard this verse from the other students, he commented, “That’s fine, all right, but not perfect.” The other students laughed at him saying, “What does an ordinary man like you know? Don’t talk crazy.” Hui-neng replied, “You don’t believe me? I would like to add a verse.” The other students looked at each other and laughed without giving a reply. That night, Hui-neng secretly summoned a servant boy to come with him to the hall, and asked him to write a verse on the wall next to the one written by Shen-hsiu:

Enlightenment basically has no tree,

And the clear mirror has no stand;

Originally there is not a single thing;

Where can dust gather?

When the fifth patriarch saw this verse, he said, “Who composed this? He has not seen the essence either.” Everyone heard what the patriarch said, so they didn’t pay the verse any mind. That night, however, the fifth patriarch surreptitiously went to the mill and asked Hui-neng, “Is the rice whitened yet?” Hui-neng answered, “It is whitened, but has not had a sifting yet.” (The word for “sifting” has the same sound as the word for “teacher.” This dialogue between teacher and student has a double meaning throughout.) The fifth patriarch then knocked the pestle three times with his staff, and so Hui-neng entered his room in the third watch of the night, where he received the mental transmission of the fifth patriarch. At that time the fifth patriarch repeatedly examined Hui-neng’s initial understanding of the meaning of “one should enliven the mind without dwelling on anything,” whereupon he penetrated all the way through to great enlightenment on hearing the patriarch’s words. Then Hui-neng said, “All things are not apart from our intrinsic nature. Who would have expected that our intrinsic nature is inherently pure? Who would have expected that our intrinsic nature is basically unborn and unperishing? Who would have expected that our intrinsic nature is fundamentally complete in itself? Who would have expected that our intrinsic nature is basically immovable? Who would have expected that our intrinsic nature can produce all things?” The fifth patriarch answered, “If you do not know the fundamental mind, study of doctrine is useless. If you do know the fundamental mind and see your own basic nature, then you are called a great man, a teacher of celestials and humans, a Buddha.” Then he handed on the robe and bowl, making Hui-neng the sixth patriarch of the spiritual lineage of Chinese Zen. After the fifth patriarch, Hung-jen, had transmitted the mind seal, that very night he saw the sixth patriarch Hui-neng off on his way across the river to go south. Personally picking up the oar, he said, “I am ferrying you across!” But the sixth patriarch replied, “When deluded, one is ‘ferried across’ by a guide; when enlightened, one ferries oneself across. Although the expression ‘crossing over’ is the same, the usage is different. I have received the teacher’s communication of the Dharma, and have now attained enlightenment; it is only appropriate that I cross over by myself, of my own nature.” Hearing this, the fifth patriarch acceded, “So it is, so it is! Hereafter the Buddha Dharma will flourish through you.” After this, the fifth patriarch stopped giving lectures. The whole community wondered about this, and asked about it, to which the fifth patriarch replied, “My Way has gone! Why inquire after it anymore?” Therefore the students asked, “Who got the robe and the Dharma?” The fifth patriarch replied, “The able one got them.” Now the community got together to discuss this. Since the worker Lu was named (Hui-)neng, which means “able,” they decided that he must have received the Dharma and slipped away in secret. Therefore, they agreed to pursue him. After two months of searching, one of the party in pursuit, a former military leader who had left society to become a monk, a man named Hui-ming, went ahead and caught up with the sixth patriarch just as he reached the Ta-yu Range. The sixth patriarch took the robe and bowl and tossed them onto a rock and said, “This robe just symbolizes evidence of truthfulness, that is all; why fight over it?” Hui-ming then tried to pick up the robe and bowl, but found that he could not even move them. He said, “I came for the Dharma, not for the robe!” The sixth patriarch responded, “Since you came for the Dharma, you should stop all entanglements and not give rise to a single thought; then I will explain it for you.” Hearing this, Hui-ming stood still for a very long time; then the sixth patriarch finally said, “Don’t think of good, don’t think of evil: at this very moment, what is your original face?” Hui-ming attained great enlightenment at these words. He also asked, “Is there any other secret message aside from the esoteric meaning of the esoteric words you have just spoken?” The sixth patriarch said, “What I have told you is not a secret. If you look into yourself, you will find the secret is in you.” Hui-ming then climbed down the mountain and claimed he had found no trace of anyone up on the ridge, and induced the posse to disperse. After this, the sixth patriarch lived in anonymity among a group of hunters in south China. It was not until fifteen years later that he finally emerged from hiding and went to Fa-hsing monastery in Canton province, where the priest Yin-tsung happened to be lecturing on the Nirvana sutra. There he took shelter under the eaves. One evening, as the wind was causing the monastery banner to flap noisily, two monks were debating about it: one said that it was the banner moving, the other said it was the wind moving. They kept on arguing ceaselessly, so the sixth patriarch commented, “It is not the wind moving, and it is not the banner moving either; it is your minds moving.” Because of this he was recognized by the priest Yin-tsung, who announced that he had found the sixth patriarch of Zen. Gathering the whole community, the priest shaved Hui-neng’s head, invested him with the precepts, and ordained him as a monk. Subsequently, he lived at Ts’ao-ch’i and spread the Way of Zen widely. This is a brief history of the enlightenment and teaching of the sixth patriarch of Zen. Based on this story, I will present three issues for study, to enable everyone to avoid further misinterpretations in the understanding of Zen studies and in the investigation of Chinese cultural and philosophical history.

* * *

The First Issue

The first issue has to do with the sixth patriarch’s enlightenment, clarifying the mind and seeing its essential nature, along with two expressions in Shen-hsiu’s verse. In the Altar Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, which has come down through history in several different versions, as well as in the records of the various texts of the Zen school, there are stories about the sixth patriarch’s first enlightenment that are not very much different from one another. In Chinese Zen, beginning with the fifth patriarch Hung-jen, people were instructed to recite the Diamond Prajnaparamita sutra as a means of entering the Way, thus changing Great Master Bodhidharma’s didactic method of using the Lankavatara sutra to seal the mind. This can only be called a change in the method of instruction; there is no difference at all in the essential message of Zen. The main import of the Diamond sutra is to clarify the mind and see its essential nature. Here and there it explains the truth of essential emptiness as realized by prajna. The method of cultivating practice to seek realization therein emphasizes the three words ”skillfully guarding mindfulness.” It explains the real character of essential emptiness, saying, “the past mind cannot be apprehended, the future mind cannot be apprehended, the present mind cannot be apprehended.” The goal is perfect knowledge of “enlivening the mind without dwelling on anything.” For the sake of obtaining a general understanding of the Zen principle of governing the mind, I will presently use modern concepts to make a comparatively easy and lucid explanation. This can also serve as an instructional basis for cultivating practice, because it is a simple and swift method of cultivating mind and nurturing its essential nature.

Step One

First we have to quietly and calmly observe and examine our own inner consciousness and thoughts, and then make a simple analysis in two parts. The first part consists of the thoughts and ideas produced from sensory feelings like pain, pleasure, fullness and warmth, hunger, cold, and so on. All of these belong to the domain of sensory awareness; from them are derived activities of cognitive awareness, such as association and imagination. The other part consists of consciousness and thought produced by cognitive awareness, such as vague emotions, anxieties, anguish, discriminating thoughts regarding people, oneself, and inner or outer phenomena, and so on. Of course the latter part also includes intellectual and scholastic thinking, as well as the very capacity one has to observe one’s own psychological functions.

Step Two

The next step comes when you have arrived at the point where you are well able to understand the activity of your own psychological functions. Whether they be in the domain of sensory awareness or in the domain of cognitive awareness, they are each referred to generally as a single thought: when you can reach the point where in the interval of each thought you can clearly observe each idea or thought that occurs to your mind, without any further absentmindedness, unawareness, or vagueness, then you can process them into three levels of observation. Generally speaking, the preceding thought (thinking consciousness) that has just passed is called the past mind, or the prior thought; the succeeding thought (thinking consciousness) that has just arrived is called the present mind, or the immediate thought; while that which has yet to come is of course the future mind, or the latter thought. However, since the latter thought has not yet come, you do not concern yourself with it. But you must not forget that when you take note that the latter thought has not yet come, this itself is the present immediate thought; and the moment you realize it is present, it has at once already become the past.

Step Three

Now the next step is when you have practiced this inner observation successfully for a long time. You watch the past mind, present mind, and future mind with lucid clarity and then develop familiarity with the state of mind of the immediate present, when the past mind of the former thought has gone, and the future mind of the latter thought has not yet come. This state of mind in the instant of the immediate present then should subtly and gradually present an open blankness. But this open blankness is not stupor, lightheadedness, or like the state before death. It is an open awareness that is lucid and clear, numinous and luminous. This is what the Zen masters of the Sung and Ming dynasties used to call the time of radiant awareness. If you can really arrive at this state, you will then feel that your own consciousness and thinking, whether in the domain of sensory awareness or in the domain of cognitive awareness, are all like reflections on flowing water, like geese going through the endless sky, like the breeze coming over the surface of water, like flying swans over the snow: no tracks or traces can be found. Then you will finally realize that everything you think and do in everyday life is all nothing more than floating dust or reflections of light; there is fundamentally no way to grasp it, fundamentally no basis to rely upon. Then you will attain experiential understanding of the psychological state in which “the past mind cannot be apprehended, the future mind cannot be apprehended, the present mind cannot be apprehended.”

Step Four

Next after that, if you really understand the ungraspability of the past, present, and future mind and thought, when you look into yourself it will turn into a laugh. By this means you will recognize that everything and every activity in this mind is all the ordinary person disturbing himself. From here, take another step further to examine and break through the pressure produced by biological sensation and the physical action and movement stimulated by thought, seeing it all as like bubbles, flecks of foam, or flowers in the sky. Even when you are not deliberately practicing self-examination, on the surface it seems like all of this is a linear continuity of activity; in reality what we call our activity is just like an electric current, like a wheel of fire, like flowing water: it only constitutes a single linear continuity by virtue of the connecting of countless successive thoughts. Ultimately there is no real thing at all therein. Therefore you will naturally come to feel that mountains are not mountains, rivers are not rivers, the body is not the body, the mind is not the mind. Every bit of all of this is just a dreamlike floating and sinking in the world, that is all. Thus you will spontaneously understand “enlivening the mind without dwelling on anything.” In reality, this is already the subtle function of “arousing the mind fundamentally having no place of abode.”

Step Five

Next, after you can maintain this state where you have clarified the consciousness and thinking in your mind, you should preserve this radiant, numinous awareness all the time, whether in the midst of stillness or in the midst of activity, maintaining it like a clear sky extending thousands of miles, not keeping any obscuring phenomena in your mind. Then when you have fully experienced this, you will finally be able to understand the truth of human life, and find a state of peace that is a true refuge. But you should not take this condition to be the clarification of mind and perception of essential nature to which Zen refers! And you should not take this to be the enlightenment to which Zen refers! The reason for this is because at this time there exists the function of radiant awareness, and you still don’t know its comings and goings, and where it arises. This time is precisely what Hanshan, the great Ming dynasty master, meant when he said, ”It is easy to set foot in a forest of thorns; it is hard to turn around at the window screen shining in the moonlight.” In all of what I have said here, I have provisionally used a relatively modern method of explaining the conditions of human psychological activities and states. At the same time I have used this to explain what transpired when the sixth patriarch of Zen experienced an awakening on hearing someone recite the line of the Diamond sutra which says, “Enliven the mind without dwelling on anything.” If through this you can understand the process of inner work and mental realization represented by the verse composed by the sixth patriarch’s senior colleague Shen-hsiu, “The body is the tree of enlightenment, the mind is like a bright mirror stand; wipe it off diligently time and again, not letting it gather dust,” then you can thereby know the sixth patriarch’s realm of mental realization as represented by his verse, “Enlightenment basically has no tree, and the bright mirror has no stand; originally there is not a single thing, so where can dust gather?” If you make a comparison between these two, you will naturally be able to understand why the fifth patriarch Hung-jen summoned the sixth patriarch to his room in the third watch of the night and entrusted him with the robe and bowl. However, “Originally there is not a single thing, so where can dust gather,” still represents his attainment before he received the transmission of the robe and bowl. Don’t forget the states mentioned above, because the state of “originally there is not a single thing” is like the realm of apricot blossoms in the snowy moonlight, which although clear and refined, is after all only one side of the matter, the silent cold of empty silence devoid of any living potential. The time the sixth patriarch made a complete breakthrough to great enlightenment was when he went into the fifth patriarch’s room in the third watch of the night, and the fifth patriarch questioned him closely about “enlivening the mind without dwelling on anything,” forcing him to go a step further to understand thoroughly the ultimate basis of the essential nature of mind. That is why he said, “Who would have expected that intrinsic nature is fundamentally pure of itself? Who would have expected that intrinsic nature is fundamentally unborn and unperishing? Who would have expected that intrinsic nature is fundamentally complete in itself? Who would have expected that intrinsic nature is fundamentally immovable? Who would have expected that intrinsic nature can produce myriad phenomena?” This finally represents the realm of immediacy and enlightenment in the “sudden enlightenment at a word” spoken of in Zen. But it will not do to forget how the sixth patriarch lived in hiding among a group of hunters after that, spending fifteen years at sustained cultivation after his enlightenment. By this it can be understood how the Lankavatara sutra brings up both the sudden and the gradual, and Zen includes both the sudden and the gradual. As it is said in the Surangama sutra, “The principle is to be understood all at once; then, using this understanding to clear them up, phenomena are to be worked on gradually, exhausted through a step-by-step process.” This indicates the equal importance of sudden and gradual. Nowadays people who talk about Zen studies cling to this one phrase “originally there is not a single thing,” and are liable to do just about anything; it’s a wonder they don’t fall into the views of crazy Zen! You must know that Zen actually has a rigorous process of practical work, and is not a matter of empty talk or wild self-approval; only then can you approach authentic Zen.

The Second Issue

The second issue has to do with the expression “don’t think of good, don’t think of evil.” In the story of the sixth patriarch’s enlightenment, I spoke of what transpired when the monk Hui-ming caught up with the sixth patriarch on the Ta-yu Range and declared he had come for the Way rather than to take the robe and bowl. The sixth patriarch therefore first told him, “Don’t think of good, don’t think of evil.” After quite a long while, the sixth patriarch then asked him, “At precisely this moment, what is your original face?” In other words, he was asking, “When you are not thinking of good or evil in your heart, and there is no thinking going on in your mind at all, what is your original face?” Because very few of the later readers of the Altar Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch have done any real Zen work, they overlook the meaning of the expression “quite a long while.” And they also take the interrogative “what” in “what is your original face” and read it as if it were the demonstrative “that.” Thus they suppose that when this mind is “not thinking of good and not thinking of evil,” this itself is the fundamental basis of the essential nature of mind. Hence there has come to be the misunderstanding that recognition of the absence of good and evil is itself the essence of mind. If this be so, can mentally retarded people, mentally ill people who have lost the power of coherent thinking, and brain damaged people all be considered to have attained the realm of Zen? Thus it should be clear to you that when you reach the point at which you are “not thinking of good and not thinking of evil,” only when the open clarity of your mental state produces the realm of all subtle understanding can it be considered the initial enlightenment of Zen. And this can only be said to be initial enlightenment; this is the beginning of what the sixth patriarch referred to as the secret being in you. If people misunderstand this story, they are really in danger of fooling themselves and misleading others; that is why I have made a particular point of presenting this to you for you to reflect upon.

The Third Issue

The third issue has to do with “it is not the wind moving, nor is it the pennant moving; it is your minds moving.” This is the sixth patriarch’s first exercise of his potential after having just emerged from the mountains, and it is an example of what was called acuity of mind in later Zen. It is a kind of subtle saying characteristic of the situational teaching method; it is not the essential teaching of Zen that points to clarification of mind and perception of its nature. It is equivalent to the saying that “wine does not intoxicate people, people intoxicate themselves; sex does not delude people, people delude themselves,” which are similar witticisms. “When the clouds race by, the moon runs swiftly; when the shoreline shifts, the boat is traveling.” Can you tell who is moving and who is still? If you are asleep, even if “on both banks the cries of the monkeys go on and on; the light boat has already passed the myriad mountains,” nevertheless you do not see or hear; so how could you compose such a marvelous expression? This is what is referred to in the Only Consciousness doctrine of Buddhism as the wind of objects blowing the waves of consciousness, the principle that all feelings and thoughts are dependent on something else, stirred up by the wind of external objects. It is not the essence of mind of Zen Buddhism, the completely real nature of mind that has the same root as the universe and all things. Some people often take up the saying “it is your minds moving,” from the story of the wind and the pennant, and equate it with having attained complete understanding of the mind teaching of Zen. That is really a hundred and eighty thousand miles from Zen. If it were so, would modern psychological analysis not be sufficient to reach the realm of Zen? What further need would there be to talk about Zen? If you look at the great Zen masters of the T’ang and Sung dynasties in terms of this manner of understanding, you would certainly have to scorn Zen as a useless practice. Just like “a row of white herons rising into the blue sky,” the farther the flight, the more remote it becomes!

[The Story of Chinese Zen, by Master Nan Huai-chin, translated by Thomas Cleary, published by Charles E. Tuttle (Tuttle Library of Enlightenment), 1995.

* * *

Further Reading:

The Platform Sutra: Translation by Wong Mou-lam & C. Humphreys

The Platform Sutra: Translation & Commentary by P. Yampolsky

Commentary on the Platform Sutra by Ven. Sheng-Yen

The Platform Sutra: Translation by John McRae

The Platform Sutra – many different texts, translations and articles

The Altar Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, translation by Charles Luk (Lu Kuan-yu): Part 1. Part2.

Textual study of the Platform Sutra

Excerpts from the Platform Sutra translated by Red Pine (Bill Porter)

You must be logged in to post a comment.